The Effect of Music on Sports Performance

Introduction

We’ve all seen people walking around wearing some sort of headphones, listening to their music on the move. Music is widely accessible, all you need is a phone or some form of digital storage device, and some headphones.

Music means different things to different people, but most can appreciate the change in mood brought on by their favourite tune.

For athletes, or even casual sports participants, music can often mean more – a way to get ‘fired up’ and into that state of mind that you feel you perform the best. Is this a legitimate assumption, or does music play no part in performance enhancement? Is it just all in our head?

In 2007, the USA Track & Field, the national governing body for distance racing, banned the use of headphones and portable audio players at its official races, creating the rule “to ensure safety and to prevent runners from having a competitive edge.” This rule has since been relaxed, and altered – although not retracted, mostly due to a massive backlash and flouting of the rules on mass.

Usain Bolt

The world-leading researcher on music for performance, Dr. Costas Karageorghis, who has authored over 100 studies (and will be spoken about throughout this article, says that one can think of music as “a type of legal performance-enhancing drug.”

People who compete in sporting competitions are always looking to boost their performance anyway they can (within the rules), so if simply listening to music can help us get that extra few seconds / metres / kg then it should be carefully considered.

What does music do to the brain?

The interest in the effects of music on the brain has led to a new branch of research called ‘neuromusicology’ which explores how the nervous system reacts to music.

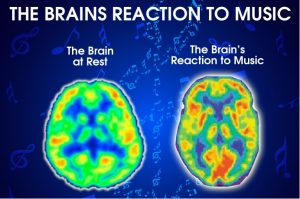

Music has been found to activate every known part of the brain, even parts that are very difficult to access through other psychological means. It improves memory, attention, physical coordination and mental development.

“When the brain is listening to music, it lights up like a Christmas tree,” Karageorghis said. “It’s an ideal stimuli because it reaches parts of the brain that can’t easily be reached.”

Listening to music activates several major brain areas at once, his research shows: the parietal lobe, which contains the motor cortex; the occipital, or visual processing lobe, the brain’s centre for rhythm and coordination; the temporal lobe, which regulates pitch, tone and structure; and the frontal lobe and cerebellum, which regulate emotion.

These brain areas are critical to athletic performance. It is in the temporal lobe that cortisol — a stress hormone — is released. I will talk about this later.

The motor cortex, which is located in the parietal lobe, regulates our body’s motor function, which helps determine how straight we throw a ball or how well we coordinate our limbs when running, and allows us to fall into our own “rhythm” as we work.

Music Boosts Brain Chemicals

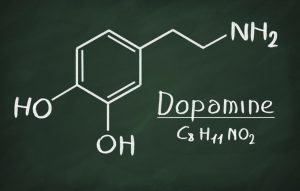

The main way music affects mood is by stimulating the formation of certain brain chemicals. Listening to music increases the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine is the brain’s “motivation molecule” and an integral part of the pleasure-reward system. It’s the same brain chemical responsible for the feel-good states obtained from eating chocolate and ‘runner’s high’.

Interestingly, it has been found that you can further increase dopamine production by listening to a playlist that’s being shuffled. The reason for this is that when one of your favourite songs unexpectedly comes up, it triggers a small dopamine boost.

Dopamine is particularly important for sportsmen/women due to it being an essential ingredient in the adrenal process, and the release of adrenaline.

What is Dopamine’s role in the adrenal process?

The dynamic duo – norepinephrine and epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) play an important role in the ‘fight or flight’ response, and we know when they aren’t produced in the right amounts and at the right time, things go wrong.

Dopamine and its proper synthesis and function in the body are crucial for mental and physical health on numerous levels. Dopamine is the precursor to norepinephrine and epinephrine, and also has receptors in the adrenal cortex. With this, dopamine is thus involved in how the adrenal glands work and how our bodies react to stress. Don’t ever forget that demanding workouts are most certainly seen by your body and all of its systems as stress.

Dopamine forms yet another important part of the complex adrenal system and understanding it is key to making sense of the physical and emotional changes that can occur when the adrenal system is compromised. Dopamine is most notably responsible for feelings of pleasure and euphoria. It also plays an important role in locomotion, learning, memory, and other emotions. Considering how many vital functions it is involved in, it’s no great surprise that dysregulation of dopamine is linked to diseases like schizophrenia, ADHD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, Parkinson’s, Tourette syndrome, restless leg syndrome, and possibly autism.

First, the basics of dopamine. It is a catecholamine and is considered both a hormone and a neurotransmitter, basically a chemical messenger between nerve cells. It is produced in the brain in two places: the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area. A small amount is also produced in the adrenal medulla and released in times of stress. The substantia nigra is associated with movement of the body and subsequently the tremors, akinesias (loss of voluntary movement), and rigidity of Parkinson’s disease are related to the degradation of this part of the brain.

The ventral tegmental area sends dopamine to other areas of the brain like the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex. When we are exposed to pleasurable things like chocolate, new clothes, a shiny new car, sex, or drugs, dopamine is shunted to the nucleus accumbens. This area of the brain is highly associated with pleasure, motivation, and the reward system. This becomes addictive.

Drugs like cocaine and other stimulants hit those reward centres hard and addiction is likely. There is research that also links people who are more sensitive to the dopamine-related reward system to reward-seeking behaviour and extroverted personality types. Keep this in mind if you’re ever feeling an overwhelming need to workout, even if you know you shouldn’t. Recovering from an injury, being legitimately ill, or being validly over-trained are scenarios that come to mind.

Back to the basics of dopamine: Dopamine acts as a hormone specifically in the hypothalamus. When dopamine is released it inhibits the hypothalamus from releasing prolactin. Prolactin stimulates lactation or milk production and is also involved in sexual satisfactions.

Now that we’ve discussed what dopamine is and the important role it plays in the body, let’s talk about how we produce it. Just as with norepinephrine and epinephrine, the amino acids L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine, and L-DOPA are crucial for dopamine to be synthesized in the body. Here’s the breakdown of this whole synthesis pathway:

L-phenylalanine is converted to L-tyrosine.

L-tyrosine is then converted to L-DOPA.

L-DOPA is converted to dopamine.

Dopamine will move down the conversion chain to yield norepinephrine and epinephrine.

So, in conclusion – your adrenal system, including all the hormones and neurotransmitters that go with it, is a very complex system that has the ability to greatly impact every other system in your body. Because of the massive changes it can cause in other systems, any major issues with your adrenal system can affect virtually any function in the body.

The effects to Cortisol levels

The stress hormones namely cortisol and adrenaline are secreted by the adrenal glands in response to Adrenocorticotropic hormone or ACTH. The ACTH, composed of 39 amino acids is the primary stimulation for the production for of adrenal cortisol. It is synthesized by the pituitary in the hypothalamus in the brain in response to corticotropin-releasing hormone.

The Adrenal Glands

High-intensity exercises plus energizing music of fast tempo increase the cortisol levels, while the slow, quiet, calm and classical music does the opposite. People are more likely to respond to music they like, rather than to specific frequencies without knowing which music increases or decreases the cortisol levels.

The blood cortisol levels of those with imminent surgery can be reduced by 50% with calming music, jointly chosen by the patient and music therapist.

Music has been shown to aid untrained runners to produce higher levels of cortisol, and prolonged exposure to fast music like rock or heavy metal may induce addictive cortisol levels, like coffee. It has also been demonstrated that listening to upbeat music before a game can keep athletes from choking under pressure.

How does this affect sporting performance?

Four commonly accepted ways in which this happens are:

- Dissociation through music diverts the mind

Dissociation refers to diverting the mind from sensations of fatigue that creep up and in during performance. Research has repeatedly shown how music can improve performance by drawing one’s attention away from feelings of fatigue and pain when engaged in endurance activities such as running, cycling, or swimming. In fact, sports scientists at Brunel University, a world-leading research hub on music for athleticism, have demonstrated that music can reduce your rate of perceived effort (RPE) by 12% and improve your endurance by 15%. This benefit isn’t exclusive to beginner exercisers: elite athletes use this strategy all the time.

Did you know that one of the greatest distance runners in history, Haile Gebrselassie, synched his stride to the song “Scatman” when breaking the 10,000 metre world record?

Haile Gebrselassie

It’s been shown that listening to music during exercise increases the efficiency of that activity and it postpones fatigue. This especially holds true if there is a synchrony between the rhythm of the music and the movements of the athlete themselves. In terms of muscle strength, music that is perceived to be motivating can lead to bursts of intensity. This increases your work capacity and can bring about ultra-high levels of explosive power, strength, and productivity. Think of its influence on sprints, high jumps, powerlifting and plyometrics.

- Music promotes flow states for internal motivation

‘Flow’ involves an altered mental state of awareness during activity. Even though it is a feeling of energised focus it seems the mind and body function on ‘auto-pilot’ with minimal conscious effort. Some coaches and athletes refer to this as being ‘in the zone’. It sometimes has been referred to as a spellbinding state and can actually feel trance-like. So, can you imagine how music can pair with flow for a stimulating and enhancing performance for yourself or client. Some athletes describe utilising music to aid with their mental imagery during the routine part of their activity as allowing them to be ‘in the zone’. Many athletes use music in diverse ways in order to achieve a certain level of focus and concentration before a game or competition as well. Music enables them to put aside all other outside distractions in order to concentrate and envision what they want to accomplish during the game.

- Synchronised music movements can shift your level of workout

Synchronising your music with repetitive exercise is linked to increased levels of work output. Research supports the synchronistic aspect of rhythm as an important piece in skill and performance. For example, music can balance and adjust movement, thus prolonging performance. Have you ever had that experience where listening to a faster tempo moved you along at a faster pace which enhanced the activity your were engaged in? Conversely, we then can apply this to the slower (tempo) that may be conducive to a slower or more graceful pace or need for focus. A news release from Stanford University reports researchers assert specific pieces of music could enhance concentration or promote relaxation. Think what’s needed in figure skating, the skill in archery, a free throw in or a golf putt. Similarly, sedating music can be particularly helpful with pre-competition anxiety and nerves.

- Music evokes emotions that enrich your enjoyment

Several studies have linked music with positive feelings and memories. Music can boost internal motivation by triggering good emotions, helping you experience much greater pleasure from the activity. This is magnified when a piece of music reminds you of an aspect of your life that is emotionally significant. Why does it matter? Researchers believe that these factors have the power to increase your adherence to an exercise programme in the long run. Stickiness is crucial for unconditioned individuals and for those who are in a rehabilitation programme that involves exercise, such as physiotherapy, the treatment of chronic pain, or a heart condition. So, if music can be intentionally added as part of a training programme, think how much more inclined a person will be to come back.

What does this mean?

For those who exercise, music can be a way to distract oneself from the physical activity they are enduring and to try to lessen their consciousness of fatigue. However recent studies have seen that music has a much greater effect than just providing a distraction. Studies conducted by sports psychologists have determined that music has a great impact on the performance level of an athlete. It has been suggested that the correct type of music can heighten an athlete’s performance by up to twenty percent. A sports psychologist at Brunel University, Dr. Costas Karageorghis, has done studies to see the results of synchronous music and asynchronous music. Synchronous music, music that has a clear and steady beat, was what was shown to elevate a person’s performance by twenty percent whereas asynchronous music, background music, was shown to calm the nerves of athletes by as much as ten percent.

- Rendi et al. (2008) investigated the impact of fast and slow-tempo music on 500-m rowing sprint performances. Twenty-two rowers performed 500-m sprints 3 times: rowing without music, rowing to slow music, and rowing to fast tempo music. Strokes per minute (SPM), time to completion, (TTC), and rated perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded.

Although RPE did not differ between the rowing conditions, TTC was shortest in the fast music condition. Further, shorter TTC was observed in the slow music condition in contrast to the control condition, indicating that slow music also enhanced performance.

The strongest treatment effects emerged, however, in the examination of the SPM that were significantly higher during rowing to fast music in comparison with rowing to slow music or no music. These results suggest that fast music acts as an external psyching-up stimulus in brief and strenuous muscle work.

How to make the most of music

In support of theoretical research, many famous athletes have been seen using music to enhance their performance. For instance, the American swimmer Michael Phelps, who is the most successful Olympian of all time, reportedly listened to hip-hop music before his races in order to get focused and psyched up. This involved narrowing his attention to focus on rapper Lil’ Wayne’s lyrics “Yes, I’m the best, and no I ain’t positive, I’m definite I know the game like I’m reffing it”

Michael Phelps

When accompanying training and workouts with music, researchers have suggested assembling a wide selection of familiar tracks that meet the following six criteria in order to achieve benefits to performance:

(a) strong, energising rhythm; (b) positive lyrics having associations with movement; (c) rhythmic pattern well matched to movement patterns of the athletic activity; (d) uplifting melodies and harmonies; (e) associations with sport, exercise, triumph, or overcoming adversity (e.g.. Heather Small’s ‘Proud’, used in the London 2012 Olympic bid); and (f) a musical style or idiom suited to an athlete’s taste and cultural upbringing. Choose tracks with different tempos, to coincide with alternate low, medium, and high-intensity training.

Research has shown that music can be most effective when played at the point when people reach a plateau in work output. When devising your own music playlist for training, it is important to take into consideration the type of mindset you want to achieve for a particular workout. For example, British rowing Olympic gold medallist James Cracknell, used the persistent rhythms of the Red Hot Chili Peppers during training and his pre-event routine. Thus, if your movements are steady and rhythmic, the music should not have fluctuations in tempo; rather, it should parallel the speed of your own movements.

For example, if you are warming up on a gym bike at a pace of approximately 65 bmp, commercial dance music, typically in the range of 120 to 130 bmp, is ideal as you can take half a pedal revolution to each beat of the music (Karageorghis & Terry, 2011).

Musical Selection recommendations for the Components of a Typical Training Session

| Workout component | Track title | Artist | Tempo (beats per minute) |

| Mental Preparation | Thrift Shop | Macklemore Feat Wanz | 95 |

| Warm-up activity | Proud | Heather Small | 103 |

| Stretching | You Know You Like It | Aluna George | 92 |

| Strength component | Bounce | Calvin Harris | 130 |

| Endurance component | Louder | DJ Fresh | 138 |

| Cool-down activity | Fine China | Chris Brown | 104 |

*Adapted from C.I Karageorghis and P.C Terry, 2011, Inside sport psychology (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics).

What Music is The Best to Listen to?

To study how music preferences might affect functional brain connectivity – the interactions among separate areas of the brain, Burdette and his fellow investigators used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which depicts brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. Scans were made of 21 people while they listened to music they said they most liked and disliked from among five genres (classical, country, rap, rock and Chinese opera) and to a song or piece of music they had previously named as their personal favourite.

Those fMRI scans showed a consistent pattern: The listeners’ preferences, not the type of music they were listening to, had the greatest impact on brain connectivity — especially on a brain circuit known to be involved in internally focused thought, empathy and self-awareness. This circuit, called the default mode network, was poorly connected when the participants were listening to the music they disliked, better connected when listening to the music they liked and the most connected when listening to their favourites.

The researchers also found that listening to favourite songs altered the connectivity between auditory brain areas and a region responsible for memory and social emotion consolidation.

“Given that music preferences are uniquely individualized phenomena and that music can vary in acoustic complexity and the presence or absence of lyrics, the consistency of our results was unexpected,” the researchers wrote in the journal Nature Scientific Reports (Aug. 28, 2014). “These findings may explain why comparable emotional and mental states can be experienced by people listening to music that differs as widely as Beethoven and Eminem.”

Is it really as simple as that?

A study done to investigate the psychological effects of music on performance was done at Milligan College in Tennessee. To set up the experiment, the term ‘priming’ must first be explained.

“By priming participants with particular instructions prior to the experiment, a researcher can actually heighten the likelihood that thoughts, with much the same meaning as the stimulus, will come to mind. When participants are told that a stimulus will affect them in some way, they will in fact behave accordingly. This priming is particularly effective with regards to physical exercise performance”

Priming is the perfect way to test the effects of music on athletes. By pre-conditioning the study subjects to certain expectations and attitudes, the raw effects of music can be measured.

For this experiment, ninety-one college students were invited to run several laps while listening to music for a certain duration. The ninety-one students were divided into three groups. Members of Group A (n=25) were told that music would heighten their athletic performance immensely. Participants of Group B(n=19) were told that music would greatly diminish their ability to perform well. And those in Group C (n=47), the control, were not given any information on the impact that music would have on their performance. The results were fairly significant and demonstrated that preconceived notions on the effects music are key to actually seeing positive effects from music during athletic performance.

The effectiveness of the music was analysed by measuring the mean number of laps each group was able to complete in the given time. For Group A, the group that was told music would enhance their performance, the mean number of laps completed was 6.38. Group B, that was told the music would negatively impact their performance, the mean number of laps was 4.97. And Group C, given no information, had a mean number of 5.55 laps.

The most interesting and significant part of this study was the fact that two groups, A and B, both listed to music, were told completely different information and performed very differently. This demonstrates that it is not the music that is changing the level of athletic performance achieved but it is that knowledge that an outside force might have the ability to change one’s performance level that actually made an impact.

This is a clear indication of the power that the brain has on affecting a person’s physical self. Similar to the sugar pill, the impact that music can have on a person is a preconceived notion; music itself does not have the power to induce athletic prowess.

It must be noted, however that the study does not indicate whether the runners were split randomly, or by some other means, whether there was a mix of genders, or the running abilities & fitness of the participants.

To contrast – One study by M. Eliakim et al. (2007) aimed to determine the effect of arousing music during warm-up on anaerobic performance in elite national level adolescent volleyball players. Twenty-four players (12 males and 12 females) performed the Wingate Anaerobic Test following a 10-minute warm-up with and without music (two separate occasions, random order). During warm-up with music, mean heart rate was significantly higher. Following the warm-up with music, peak anaerobic power was significantly higher in all volleyball players (10.7 ± 0.3 vs. 11.1 ± 0.3 Watts/kg, p < 0.05, without and with music, respectively). Gender did not influence the effect of music on peak anaerobic power. Music had no significant effect on mean anaerobic output or fatigue index in both genders. Music affects warm-up and may have a transient beneficial effect on anaerobic performance.

Are there any negatives to listening to music?

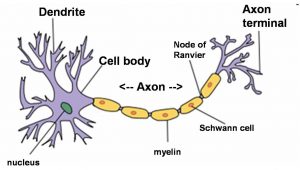

Well, yes there could be. Rock Music for example harmed Dendrite patterns.

In one study, the ability of mice to navigate a food maze was tested by continuously playing the music at low volumes to eliminate behavioural changes.

Those subjected to either silence or Strauss waltzes (relaxing melodies) had no problem in the maze with a little advantage for the latter. Those exposed to voodoo drumming performed worse and finally became confused, hyperactive, aggressive and even cannibalistic.

The highly abnormal neuronal growth patterns with excessive Dendrite branches growing out in all directions and having few connections with other neurons were found in the hippocampus region of the brains of these mice. This region acts in learning and memory formation.

Due to an increase in dendrite branching, the messenger RNA involved in memory formation too increased. It meant that the brain tried to analyse the sound stimulus, but failed.

What is Dendrite

The word Dendrite has come from dendron which means a tree in Greek. These branched projections of neurons propagate the electro-chemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or from soma of the neuron, from which the dendrites project.

Different inputs like lifestyle, stress and environment affect and continuously reshape the branching pattern of dendrites. Proper growth and branching of dendrites is crucial for the functioning of the nervous system as these are the connections to other nerve cells. Defects in dendrite growth cause severe neuro-developmental disorders like mental retardation etc.

What to draw from this is rather unclear, I’m not saying that prolonged exposure to rock music may make you want to turn cannibal – but short bursts of this type of music (to elicit the responses covered earlier) may be a better tactic.

Conclusions

Although there may be more research that needs to be done, it has been shown that an individuals own favourite music can influence them to an increase in sporting performance. This is through the effect it has on producing Dopamine, the lead on to Ephedrine (Adrenaline) production, the adherence of a positive mood & rejection of negative states of mind.

Enjoyable music will help you get ‘in the zone’ and focus on what you are going to do, even blocking out pain from injuries or niggles.

The type of music is not important, but the use of musical lyrics that back up your chosen goal will help. Even music that you are indifferent to is better than silence, or ‘general background noise’.

Music, lyrics and tones are already being used by elite level athletes to increase performance, I don’t think it will be too long before this is more widely used by coaches – and perhaps even ‘prescribed’ to an athletes’ personal preferences. Music may even be made specifically to enhance certain aspects of sport, but for now – just listen to what makes you feel good and you will improve in your target area.

References

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-2006-924360

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2466/pms.1996.83.3f.1347

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1076/apab.111.3.211.23464

https://journals.humankinetics.com/doi/abs/10.1123/tsp.22.2.175

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10413200902795091?journalCode=uasp20&#.Un0q8ZRUNcS

https://bebrainfit.com/music-brain/

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/04/170412181341.htm

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/12/111205081731.htm

https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/The-Effect-of-Music-on-Human-Health-and-Brain-Growth

https://thehealthsciencesacademy.org/health-tips/music-can-enhance-athletic-performance/

http://believeperform.com/performance/how-to-benefit-from-music-in-sport-and-exercise/

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/can-music-make-you-a-better-athlete

http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/exchange/gflaherty/effects-music-athletic-performance

https://breakingmuscle.com/fitness/understanding-our-adrenal-system-dopamine

Simpson SD, Karageorghis CI. The effects of synchronous music on 400-m sprint performance. J Sports Sci. 2006 Oct;24(10):1095-102

Brooks, Kelly, and Kristal Brooks. “Enhancing sports performance through the use of music.” Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, vol. 13, no. 2, 2010, p. 52+. Academic OneFile, Accessed 12 Mar. 2018.