Resistance Training for Adolescents & Pre-adolescents

Introduction

Growing up I competed in several different sports, all to reasonable levels. Swimming however, was the sport that I excelled at – I have probably mentioned this before so I won’t go into any more detail here. The reason I mention it is that I was having some cutting-edge training by some very good coaches at the time from the age of eight up to around 18.

From age eight to 14 the training was all pool based; technique, stamina, speed & power etc. Some emphasis was put on stretching and recovery and a very small amount on nutrition – but the concept of any land-based training was not even considered for the majority. It was seen as dangerous, risky and not something you ‘should’ do at a young age.

By age 15 things were starting to change and resistance training was just starting to be talked about. Of course, the elite (adult) athletes had been supplementing with weight-training for decades but it was thought that weight / resistance training would impact negatively on our immature bodies so was left until we hit our late teens.

There were exceptions of course, and some of the competitors I would race against would have been in the weights room and you could definitely tell.

Nowadays it’s becoming more and more usual to see adolescents and pre-adolescents using resistance training to improve their sport – especially in the USA, and also to set the basis for a future in strength sports.

Was all this worry about damaging our bodies justified? There have been stories about damaging bone end plates, injury susceptibility and ‘stunting growth’ going around for years, but how much truth is in this?

The Facts

Narelle Sibte – Strength & Conditioning Coach at the Australian Institute of Sport says that resistance or weight training (as opposed to the disciplines of weightlifting or powerlifting) had not been recommended for preadolescents because of the concerns for injury and the questionable efficacy of this type of training to improve strength.

He goes onto say that for many years it was thought that pre-adolescent children were incapable of improving strength through resistance training, however over the last 25 years, several studies have shown that preadolescent children are capable of safely improving muscle strength with appropriate training regimes. A review of strength training improvements in children found that the majority of studies demonstrated strength gains between 13-30% as a result of resistance training over an 8-12 week period. K. S. Dahab & T. M. McCambridge (2009) found an even greater increase of 30% to 50% over the same time period. The key part of this is that it must be an ‘appropriate training regime’.

A. D. Faigenbaum & J. McFarland (2016) conducted an investigation to determine the effects of 8 week of resistance training on muscular strength, integrated EMG amplitude (IEMG), and arm anthropometrics of prepubescent youth.

Sixteen subjects (8 males & 8 females) were randomly assigned to trained or control groups. All subjects (mean age of 10.3 years) were of prepubertal status according to the criteria of Tanner (the Tanner scale – also known as the Tanner stages, is a scale of physical development in children, adolescents and adults). The trained group performed three sets (7-11 repetitions) of biceps curls with dumbbells three times per week for 8 weeks. Pre and post-training measurements included isotonic and isokinetic strength of the elbow flexors (biceps), arm anthropometrics, and IEMG of the biceps brachii.

They found significant isotonic (22.6%) and isokinetic (27.8%) strength gains were observed in the trained group without corresponding changes in arm circumference or skinfolds. The IEMG amplitude increased 16.8% (P < 0.05).

They observed that the control group did not demonstrate any significant changes in the parameters measured, and go onto state the early gains in muscular strength resulting from resistance training prepubescent children may be attributed to increased muscle activation.

Showing similar results, in a study by L. Sewall & L. J. Micheli in the Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics (1986) eighteen prepubescent children, two at Tanner Stage II and the remainder at Tanner Stage I, were studied.

The examination included anthropometric upper and lower extremity strength and flexibility measurements. The study group participated in progressive resistive strength training sessions on machines three times per week, and had a mean increase in strength of 42.9%, whereas strength in the control group increased 9.5% (p less than 0.05).

The study group were shown to have a mean increase in flexibility of 4.5% compared with 3.6% in the control group, and showed a mean decrease in body weight during the training period of 0.51% and then gained 3.48% over the subsequent 9 weeks. The control group’s body weight increased an average of 6.66% during the 18 weeks.

It was concluded that prepubescent children can make significant gains in muscle strength in response to progressive resistive training.

The primary concerns regarding strength training are safety and its effectiveness. Numerous health care and fitness professional groups—including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Sports Medicine, the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, and the National Strength and Conditioning Association—agree that a supervised strength training program that follows the recommended guidelines and precautions, and overseen by a qualified coach is safe and effective for children.

Strength has been found to increase twofold between the ages of 7 and 12 years, with average values slightly greater in boys. Although fairly obvious that strength training will improve an adolescent athlete’s performance in weight lifting and powerlifting, and it could be argued that failure to start resistance training before 16 may be detrimental to any sport/strength career longevity.

Conversely, despite theoretical benefits, W. J. Kraemer et al (1997) & K. Hakkinen et al (1989) claim that scientific studies have failed to consistently show that improved strength enhances running speed, jumping ability, or overall sports performance. Although it could be argued that this date is now out of date and has been disproven.

A. D. Faigenbaum & J. E. McFarland (2016) state that these benefits will be realised only if youth have developed adequate levels of muscular fitness and movement skill competency. A certain level of force production and force attenuation is needed to perform movement skills, and therefore, the importance of enhancing muscular fitness should be considered foundational to long-term physical development.

At puberty, the strength of girls plateau’s, while stimulated by testosterone; muscle strength in boys increases. In initial stages of training, girls have the potential to improve more than boys, as generally speaking, they start from a lower status. Going back to personal experience again, I found that girls of the same level as me who I trained with would be as fast, if not faster than me until the age or around 12-14 (puberty) which could be a bit disconcerting.

This means that gains from strength training for preadolescents are generally attributed to the nervous system and motor learning, rather than hormones. Preadolescents also make similar relative gains in strength compared to later stages of development but usually demonstrate smaller absolute strength increases following strength training.

These findings have implications for injury prevention and performance enhancement for young athletes.

Injury prevention

Common overuse injuries such as tendonitis can result from excessive volume of training and competition, particularly when loads are increased dramatically in a short period of time. The growing athlete may be particularly susceptible to such injuries because of diminished flexibility and muscle-tendon strength mismatches due to the bodies staggered development.

Assessing the perceived potential damage to the growth plates of long bones – even studies nearly 30 years ago by Ramsey J. et al (1990) show that growth plates are not affected – either positively or negatively – by a wide range of sports and training modalities. In those studies where injuries were recorded, poor technique, excessive loading and performance of jerky/bouncy activities with rotation, were identified as contributory factors. K. S. Dahab & T. M. McCambridge (2009) found these injuries to be primarily attributed to the misuse of equipment, inappropriate weight, improper technique, or lack of qualified adult supervision, again showing the importance of an appropriate training regime with proper supervision from a knowledgeable coach.

On the other side, some degree of bone stress via resistance training does encourage bone growth. Resistance training increases muscle strain, strain rate and compression, which are all important in bone modelling. The low-level stresses of weight training were found to be no worse than actually completing sport specific training (jumping, hitting, running, etc) or competing in sport itself. This is a very important finding, as children are encouraged to play sports, the fact that weight training is no more risky is a big plus point.

For injury prevention, adherence to sound exercise & training principles and competent adult supervision is paramount.

Training principles

On a very basic level, when designing a training programme for anyone (including young people) a number of general principles need to be considered:

Progressive overload refers to the practise of continually increasing the stress placed on the muscle as it becomes capable of producing greater force or has more endurance. There are a number of ways in which total load can be increased. These include:

- The resistance lifted/moved can be increased

- Increase the training volume (more reps/sets, longer sessions)

- Increase training frequency (more sessions per week)

Some people suggest a 10% policy – limiting increases in training frequency, intensity and duration to no more than 10% per week. This however still seems a large amount to be increasing these factors to me.

Of all the strength training parameters, exercise intensity appears to be the second most important variable in effective program design for pre-adolescents. A general guideline suggests that intensity be moderate (approximately 10-15 reps), and that maximal lifts should be avoided. The young athlete should be able to comfortably move their own body weight before they attempt external resistance exercises. This puts an emphasis on core strength, co-ordination and proprioception. High repetitions also enable the young athlete more time to practice the techniques, assisting their skill acquisition which will help determine future advances.

It should also be noted that a failure to incorporate scheduled rest periods into the training program can also contribute to the overuse/chronic injuries.

Guidelines for Strength Training

Before a child starts a training program, the training supervisor, the child, and the parents should discuss the goals and expectations. The dangers of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing substances should be part of that discussion. Current studies in the USA report that the rate of anabolic steroid use in adolescents ranges from 1.5% to 7.6% dependant on location.

Weight training programs should be individualised on the basis of age, maturity, and personal goals and objectives. K. S. Dahab & T. M. McCambridge recommend that each training session should include a 5- to 10-minute warm-up and a 5- to 10-minute cooldown. Warm-up activities help to increase body temperature and blood flow (ie, to the musculature), whereas cooldown activities help to maintain blood flow to enhance recovery and flexibility. Programs that incorporate an aerobic component are most beneficial because they improve overall cardiovascular fitness and stimulate an increase in metabolism.

When a child or adolescent is learning a new exercise, he or she can use no-load repetitions, which places the focus on form and technique (see also, RTSC later in the article). To properly develop strength and promote flexibility, exercises should be performed through the full range of joint motion, performing larger-muscle exercises before smaller-muscle exercises. Furthermore, complex exercises are generally done before simple exercises, and multi-joint exercises, before single-joint ones. In summary, starting big and ending small is a good guideline for training.

An example of a ‘no load’, or ‘bodyweight’ squat

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) state that free weights and weight machines pose unique challenges for children and adolescents because they are usually adult-sized, and that balance and coordination are underdeveloped in preadolescents, which increases their susceptibility to injury while using free weights.

Free weights do, however, enable very small incremental increases in resistance. Weight machines often require larger weight increases, which may be inappropriate for young athletes. In addition, the lever arms on weight machines may not be sized correctly for small children. The AAP say that the primary advantage of weight machines, if they are sized appropriately, is that they may not require balance or a spotter. I would argue the opposite, and that this is a disadvantage. An exercise that requires the child to control their balance will be more beneficial and will lead to the full and in sync development of the fixator and synergist muscles along with the primary muscles.

On a very general level, K. S. Dahab & T. M. McCambridge again recommend that for each training session 6 to 8 exercises are recommended that train the major muscle groups (including the chest, shoulders, back, arms, legs and core). Balanced effort between flexors and extensors and between upper and lower body is important. The goal is to perform 2 to 3 exercises per muscle group. Youth strength training programs should start with 1 to 2 sets per exercise, with 6 to 15 repetitions in each set.

For children and adolescents, the initial load should be selected so that up to 15 repetitions can be completed with some fatigue but no muscle failure. In general, resistance can be increased by 5% to 10% when the child can easily perform 15 repetitions. If the participant fails to complete at least 10 repetitions per set or is unable to maintain proper form, then the weight may be too heavy and should thus be reduced.

Participants should rest approximately 1 – 3 minutes between sets and should strength-train 2 to 3 non-consecutive days each week for maximum results. Participants must be able to correctly demonstrate proper technique before increasing the number of sets or resistance.

It is also worth noting that stopping a strength training program, even while continuing to participate in sports, may result in a regression of strength to pretraining levels: An average of 3% of strength is lost per week once strength training is stopped and detraining begins, and children may even show a complete loss of strength gains 8 weeks after stopping a strength training regimen. J. Gomez et al (2001) say that maintenance exercises may offset these losses, but specific recommendations for maintaining strength gains have not been defined for preadolescents and adolescents.

Regarding how often children should participate in resistance training, A.D Faigenbaum carried out a study to compare the effects of 1 and 2 days per week of strength training on upper body strength, lower body strength, and motor performance ability in children.

Twenty-one girls and 34 boys between the ages of 7.1 and 12.3 years volunteered to participate in this study. Participants strength trained either once per week (n = 22) or twice per week (n = 20) for 8 weeks at a community-based youth fitness centre. Each training session consisted of a single set of 10–15 repetitions on 12 exercises using child-size weight machines. Thirteen children who did not strength train served as age-matched controls.

One repetition maximum (1RM) strength on the chest press and leg press, handgrip strength, long jump, vertical jump, and flexibility were assessed at baseline and post-training. Only participants who strength trained twice per week made significantly greater gains in 1RM chest press strength, compared to the control group (11.5 and 4.4% respectively, p < .05). Participants who trained once and twice per week made gains in 1RM leg press strength (14.2 and 24.7%, respectively) that were significantly greater than control group gains (2.4%).

On average, participants who strength trained twice per week achieved 67% of the 1RM strength gains. No significant differences between groups were observed on other outcome measures. These findings supported the concept that muscular strength can be improved during the childhood years and favour a training frequency of twice per week for children participating in an introductory strength training program.

Strength Training Myths

Numerous myths concerning strength training in children deserve discussion. The main misunderstanding concerns strength training and growth plate injuries. Participation in almost any type of sport or recreational activity carries a risk of injury.

A.D Faigenbaum, W.J. Kraemer, Cahill, et al (1996) state that a well-supervised strength training program has no greater inherent risk than that of any other youth sport or activity.

B.R Cahill also say that sports such as gymnastics and baseball, which involve repetitive impact and torque, provide a greater risk of epiphyseal injury.

Similar to rare epiphyseal injuries, soft-tissue injuries to the lower back are usually the result of poor technique, too much weight, or ballistic lifts. B.P Conroy found that while most serious injuries to the lower back occur while using free weights, participating in an organised, supervised strength training program can prevent these injuries while favourably influencing bone growth and development in youth by increasing bone mineral density.

Preventive exercise (prehabilitation) focuses on the strength training of muscle groups that are subjected to overuse in specific sports. For example, strengthening the rotator cuff and scapular muscles may reduce shoulder overuse injuries in overhead sports such as swimming. Similarly, strengthening the hamstrings and quadriceps can reduce lower extremity injuries in football athletes. Strength training can also help maintain flexibility with exercises that use the full range of motion.

ACL injuries can be devastating to a young athlete. S. M Lephart (2005) says that a simple strength training program alone may decrease an athlete’s risk of such injury. Furthermore, that strength training combined with plyometric exercises may reduce the incidence of sports-related ACL injuries in adolescent girls.

Increased strength may improve motor skills—long jump, vertical jump, 30-m sprint, squat jump, and agility runs – but may not directly improve performance. Some studies, however, have demonstrated sport-specific improvement after strength training. J. Query (1992) found an improvement in handball-throwing velocity in adolescent players has been seen with strength training, and swimming times and event-specific gymnastic performance have improved following a resistance training program.

A long-held belief by many clinicians was that strength training is not effective in children until they have significant levels of circulating testosterone, which is needed for muscle hypertrophy. In a study by Faigenbaum et al, 15 twice-weekly strength training sessions for boys and girls between the ages of 7 and 12 years produced significant strength gains in the chest press (versus age-matched controls). This again shows that children gain strength through neural adaptations, not muscle hypertrophy. Strength training in children likely improves the number and coordination of activated motor neurons, as well as the firing rate and pattern.

Prepubertal children and post-pubertal adolescents respond to strength training differently; namely, adolescents are capable of greater absolute gains owing to higher levels of circulating androgens. J. E. Peltonen (1998) says that early physical training (not necessarily strength training) has produced an increased cross-sectional area of the erector spinae, multifidus, and psoas musculature, as documented on axial MRI studies, in comparison with age-matched non-athletic controls. Muscle cross-sectional area (adjusted for body mass) directly correlated with trunk flexion and extension strength. These findings suggest that long-term sports participation alone can lead to significant muscular hypertrophy and strength gains in young athletes.

Troubling Trends in Muscular Fitness

A. D. Faigenbaum & J. E. McFarland (2016) found that youth who do not become proficient movers early in life will be less likely to participate in diverse physical activities as adults. This idea relates to Seefeldt’s original notion of a proficiency barrier whereby children who do not surpass a critical threshold of motor skill proficiency early in life will be less likely to engage in sports and physical activities later in life.

Just like the skills of reading and writing, interest and aptitude in physical activity should begin early in life with a strong focus on movement skills and physical abilities. Epidemiological findings from an international sample of children indicate that a growing number of youth are not meeting physical activity recommendations, and those with lower levels of MVPA are at increased risk of obesity. Without opportunities to develop the prerequisite levels of muscular fitness and motor skill proficiency early in life, youth are less likely to participate in games and activities with confidence and vigour later in life.

Secular trends in measures of muscular fitness in English children indicate declines in bent arm hang, sit-up performance, and hand grip strength during a 10-year period. Similar observations were reported in selected measures of muscular power (e.g., long jump and vertical jump) in Spanish adolescents and fundamental movement skills (e.g., jumping and kicking) in Australian youth. Although many factors influence time spent in MVPA during the growing years, the global pandemic of physical inactivity may be due, at least in part, to a deficiency of muscular fitness and motor skill performance in modern-day youth.

In support of this view a 2-year study of children between 6 and 10 years of age found that those with low motor competency participated less in sports and had fewer opportunities for developing motor abilities and physical fitness. Other researchers noted an increasingly widening gap in gross motor coordination between normal-weight and overweight children. Unfortunately, the divergence in performance between children with low and high levels of muscular fitness seems to persist across developmental time in the absence of targeted interventions.

Without regular opportunities to enhance their muscular strength and motor skill abilities early in life, youth will be less likely to engage in the recommended amount of daily moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and more likely to experience negative health outcomes. Of note, recent increases in the waist circumference of adolescents during periods of bodyweight stabilisation suggest that modern-day youth have more fat and less muscle than previous generations.

The Developing Nervous System

The first few years of life are characterised by rapid changes in the myelination of the central nervous system, and therefore the effects of a well-designed resistance training program can be long lasting – similar to learning a new language or playing a musical instrument, there is a unique opportunity to target strength development early in life to set the stage for greater gains in physical fitness later in life.

New insights into the design of long-term physical development programs have shown the importance of enhancing muscular strength during childhood and continuing participation in resistance training activities throughout adolescence. In fact, R. R. Lloyd & A. D. Faigenbaum show that resistance training should be a priority in youth fitness programs because muscular strength is the driving force toward performance enhancement and injury prevention.

J.J. Smith et al (2014) also state that In addition to enhancing muscular fitness and motor skill performance, various forms of resistance training can increase bone mineral density, improve cardiovascular risk factors, facilitate weight control, and prepare inactive youth for the demands of physical activity and sport.

When should it start?

Although there is no minimum age for participation in a supervised resistance training program, A. D. Faigenbaum et al say most healthy 7 and 8-year-olds are ready to follow instructions and adhere to safety rules. Any younger than this and the participant may lack the maturity and ability to be coached.

Well-designed resistance training programs enable children to improve their resistance training skill competency (RTSC). The construct of RTSC refers to the technical ability of performing a resistance exercise and involves the evaluation of movement patterns that are considered essential for the mastery of a particular exercise. RTSC relates to one’s physical development as well as one’s ability to focus, follow instructions, and execute a task properly.

The perception of RTSC as opposed to the amount of weight lifted may help to reinforce the importance of maintaining proper exercise technique and illustrates the significance of movement pattern efficiency as the appropriate criteria to measure, further showing the need for a capable coach.

The following table shows the Back Squat Resistance Training Skill Competency Checklist, this gives an example of how a child could be scored and would indicate whether they are capable of continuing the exercise and eventually progressing to a more advanced level.

Phase Desired Action Common Breakdown Points Max Earned

Check point 1. Safe exercise area Inadequate space 3

______________2. Correct starting weight Incorrect weight selection

______________3. Collars on bar (if plates Lack of collars & poorly

______________are used), and well- positioned safety rails

______________positioned safety rails

Ready position 4. Bar on shoulders and Bar positioned on neck 3

_______________upper back

_______________5. Head neutral & eyes Head facing downward

_______________forward

_______________6. Feet wider than shoulder Feet position too narrow

_______________width

Downward phase 7. Flex hips and knees Thighs not at proper depth 3

_______________8. Thighs parallel to floor Trunk begins to flex forward

_______________9. Elbows under bar, knees Knees inward or forward

_______________over feet & behind toes, Heels rise

_______________torso erect, and feet flat

Upward phase 10. Extend hips and knees Trunk begins to round 3

_______________forward

_______________11. Torso upright, elbows Elbows drift behind bar,

_______________under bar, knees over knees move inward/forward

_______________feet & behind toes

_______________12. Maintain bar control Firm grip is not maintained

_______________with firm grip until bar is

_______________racked

General 13. Responsibility Does not follow safety rules 3

demeanour 14. Resourcefulness Unwilling to solve simple

_______________________________________problems

________________15. Respect Does not cooperate with others

_______________________________________Total Points 15

Other exercises can have similar tables drawn up to decide if a participant should be trained using a certain resistance based Activity.

The four levels used to assess RTSC performance are advanced (3 points), basic (2 points), capable (1 point), and developing (0 point). The advanced level is indicative of skilled lifting performance and a genuine interest in improving personal fitness. The developing level indicates that the participant performed a skill improperly or displayed behaviour that was disrespectful or uncooperative. By recording the component scores and tallying up the total points for all phases of a specific exercise, fitness professionals can identify skills that need more instructional time and effort.

With regular exposure to resistance training early in life, children will have an opportunity to enhance their RTSC and muscular strength on a variety of exercises. Although youth with poor muscular strength and low RTSC may have difficulty performing basic resistance exercises, those with higher levels of muscular strength and skill competency will be better prepared to learn more advanced skills because they can use developing pathways that influence motor control and movement proficiency.

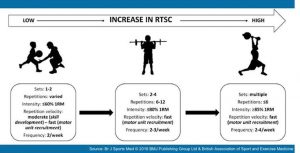

If qualified coaches assess movement mechanics and provide constructive feedback during training sessions, youth will have a unique opportunity to learn task-related activities and enhance their RTSC. If participants are beginners (low muscle strength and low RTSC), fitness professionals should prescribe a range of basic resistance exercises (e.g., squatting, pushing, or pulling movements) that enhance muscular strength while improving one’s competence to perform a variety of exercises. As youth gain competence and confidence in their ability to perform basic exercises, their capacity for resistance exercise can be improved with more advanced training programs (see the image below).

Resistance Training for Kids

Although factors such as heredity, training experience, and health habits (e.g., nutrition and sleep) will influence the rate and magnitude of adaptation that occurs, seven fundamental principles that determine the effectiveness of youth resistance training programs are the principles of:

(a) the Progression, (b) Regularity, (c) Overload, (d) Creativity, (e) Enjoyment, (f) Socialisation, and (g) Supervision.

These basic principles can be remembered as the PROCESS of youth resistance training. Although the principles of progression, regularity, and overload are well-established tenets of resistance training, the concepts of creativity, enjoyment, socialisation, and supervision are particularly applicable to the design of sustainable youth fitness programs. When working with children and adolescents, it is important to remember that the goal of the program should not be limited to increasing muscular strength. Improving motor skills, fostering new social networks, and promoting healthy behaviours in a supportive environment are equally important. This is where the art and science of youth resistance training come together – because the principles of paediatric exercise science need to be balanced with effective teaching and ongoing instruction that is developmentally appropriate for children and adolescents.

Principle of Progression

The principle of progression refers to the fact that the demands placed on the growing body must be increased gradually through time to achieve long-term gains in muscular fitness. This does not mean that heavier weights should be used every workout, but rather, that through time, the stress placed on the body should progressively become more challenging to continually stimulate adaptations and maintain interest in the program. Without a more challenging stimulus that is consistent with each individual’s needs and abilities, additional training-induced adaptations are unlikely. Although increasing the training load or performing additional sets are common methods of progression, performing novel exercises or more complex movement patters also are beneficial. This will be familiar to anyone who trains with weights / resistance training methods now – as this is a much used training protocol for people of all ages.

Principle of Regularity

Although the optimal resistance training frequency may depend on each participant’s training goals, two to three training sessions per week on non-consecutive days are reasonable for most youth. Inconsistent training will result in only modest training adaptations, and periods of inactivity will result in a loss of muscular strength and power. As mentioned earlier, the adage “use it or lose it” is appropriate for resistance exercise because training-induced adaptations in muscular fitness cannot be stored. The principle of regularity states that long-term gains in physical development will be realised only if the program is performed on a consistent basis throughout childhood and adolescence.

Principle of Overload

The overload principle is a fundamental tenet of all resistance training programs. The overload principle simply states that to enhance muscular fitness, the body must exercise at a level beyond that at which it is normally stressed. Otherwise, if the training stimulus is not increased beyond the level to which the muscles are accustomed, the participant will not maximise training adaptations. Training overload can be manipulated by changing the intensity, volume, frequency, or choice of exercise.

Principle of Creativity

The creativity principle refers to the imagination and ingenuity that can help to optimise training-induced adaptations and enhance exercise adherence. By sensibly incorporating novel exercises and new training equipment into the program, a coach can help youth overcome barriers and maintain interest in resistance exercise. Creative thinking is particularly valuable when designing resistance training programs for youth with high levels of RTSC. The fundamental principles related to the prescription of sets and repetitions should be balanced with imagination and creativity.

Principle of Enjoyment

Enjoyment is an important determinant of participation in youth fitness and sport programs. The principle of enjoyment states that participants who enjoy the experience of participating in exercise or sports activities are more likely to adhere to the program and achieve training goals.

- Csikszentmihalyi et al (2005) in their Handbook of Competence and Motivation define enjoyment as being defined as a balance between skill and challenge. If the resistance training program is too advanced, youth may become anxious and lose interest. Conversely, if the training program is too easy, then youth may become bored. Youth resistance training programs should be matched with the physical abilities of the participants for the training experience to be enjoyable. Principle of Socialisation Participation in a resistance training program can help youth interact with others in a positive and supportive manner. The principle of socialization states that gains in muscular fitness will be optimised if participants make new friends, meet other people, and work together toward a common goal.

Principle of Supervision

The principle of supervision states that the safety and efficacy of exercise programs are maximised when qualified coaches supervise activities and provide meaningful feedback throughout the training session. Not only does supervised resistance training reduce the risk of injury, but youth who participate in supervised resistance training programs are likely to make greater gains in muscular fitness. Indeed, qualified supervision is a critical component of any youth resistance training program, particularly for beginners who need to develop competence on basic exercises before progressing to more complex movements. Youth fitness specialists should be well versed in the principles of paediatric exercise science and should know how to teach, progress, and modify skill-based exercises.

Conclusion & Recommendations

It can be seen that contrary to some peoples believe, and some old wives tales, strength training for children is not only not damaging to them long term, but can be beneficial for multiple reasons. This is based on them being under close supervision by a qualified, experienced coach who has the knowledge, patients and desire to prescribe an appropriate training program for them.

- A. Ramsay et al (1990) states that strength training programs do not seem to adversely affect linear growth and do not seem to have any long-term detrimental effect on cardiovascular health. Young people who want to improve sports performance mainly will generally benefit more from practicing and perfecting skills of the sport than from resistance training though. If long-term health benefits are the goal, strength training should be combined with an aerobic training program.

Strength training for pre-adolescent athletes should focus on skills and technique. Since improvements from strength training come from neuromuscular development in this age group, this is the ideal time to teach co-ordination and stability.

Children should work at strengthening all the big muscle groups, using free-weights and body-weight movements with relatively light loads. Contrary to popular belief, machines may not be the best option for young athletes as they are designed for adults and incorrect set up may cause harm to the user.

When prescribing load for young athletes, it is always better to underestimate their physical abilities and gradually increase training load, than to overshoot their abilities and potentially injure them.

In general terms, adolescents should initially perform one to three sets of 6-15 repetitions of a variety of exercises, beginning with a frequency of 2-3 days per week on non consecutive days. There is no minimum age requirement for children undertaking resistance training programs, but participants should have the emotional maturity to accept and follow directions and should understand the potential benefits and risks associated with strength training (the RTSC method will help with this).

In a growing number of cases it would appear that the musculoskeletal systems of many young athletes are ill prepared to handle the demands of practice, games and tournament schedules – something that could be aided by an appropriate resistance training program.

Strength training programs should include a warm-up and cool-down component, and aerobic conditioning should be coupled with resistance training if general health benefits are the goal.

Specific strength training exercises should be learned initially with no load (resistance). Once the exercise skill has been mastered, incremental loads can be added, and should address all major muscle groups and exercise through the complete range of motion. If there is any sign of injury or illness from strength training should be evaluated before continuing the exercise in question.

References

Katherine Stabenow Dahab, Teri Metcalf McCambridge, Strength Training in Children and Adolescents: Raising the Bar for Young Athletes? Sports Health. 2009 May; 1(3): 223–226. doi: 10.1177/1941738109334215

A. L. Washington et al; Strength Training by Children and Adolescents, From the American Academy of Pediatrics, June 2001, VOLUME 107 / ISSUE 6

Sewall L , Micheli LJ, Strength Training for Children, Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics [01 Mar 1986, 6(2):143-146]

A.D. Faigenbaum et al (2002), Comparison of 1 and 2 Days per Week of Strength Training in Children, Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport

Ozmun JC , Mikesky AE , Surburg PR, Neuromuscular adaptations following prepubescent strength training, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise [01 Apr 1994, 26(4):510-514]

Ramsey, J. Blimkie, C. Smith, K. Garner, S. Macdougall, D & Sale, D. (1990) Strength training effects in prepubescent boys. Med Sci in Spt & Ex, 22(5): 605-614

Smith JJ, Eather N, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Faigenbaum AD, Lubans DR. The health benefits of muscular fitness for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014;44(9):1209–23.

Faigenbaum AD, Lloyd RS, MacDonald J, Myer GD. Citius, Altius, Fortius: beneficial effects of resistance training for young athletes: narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(1):3–7.

Csikszentmihalyi M, Abuhamdeh S, Nakamura J. Flow. In: Elliot A, editor. Handbook of Competence and Motivation. New York (NY): The Guilford Press; 2005. p. 598–698

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307591426_Resistance_training_for_kids_Right_from_the_Start